Free Palestine. End the genocide in Gaza.

Demonstrate. Engage in direct action. Donate.

Demand better.

A month or so ago, I mentioned an article I was writing when I had my fever. The one that got mostly deleted by a weird Substack glitch. That’s this! I started writing it, absolutely incoherent, at 10:21 pm the night I planned to release it. Then I pawed at it for like three days, lost like two-thirds of it to some computer weirdness, and abandoned it for more than a month.

I’ve finally decided to come back to the mangled shell! I’ve got lots of feelings about playing with terrain, and I’ve even got a fun little bit of real-world urgency to push me back into writing.

Actually, let’s talk about that first. No burying the lead.

I craft lots of really rad terrain, and for the first time ever, I’m selling it! Last Saturday I was a vendor at Cutie Party, a chill little maker’s-market here in Seattle. I got to sell some of my work, I got to meet some incredible artists, and I got so excited to do it again. If this article gets you interested in using terrain in your game, come and see me at Cutiefest June 22nd or 23rd!

But why would you want terrain? That’s what we’re talking about here today. How can terrain help to elevate your D&D campaign, when should you use terrain and when shouldn’t you, and how can you start building your terrain collection in an accessible way? Hopefully it’s about nine-parts advice to one-part sales pitch.

But first, let’s get on the same page

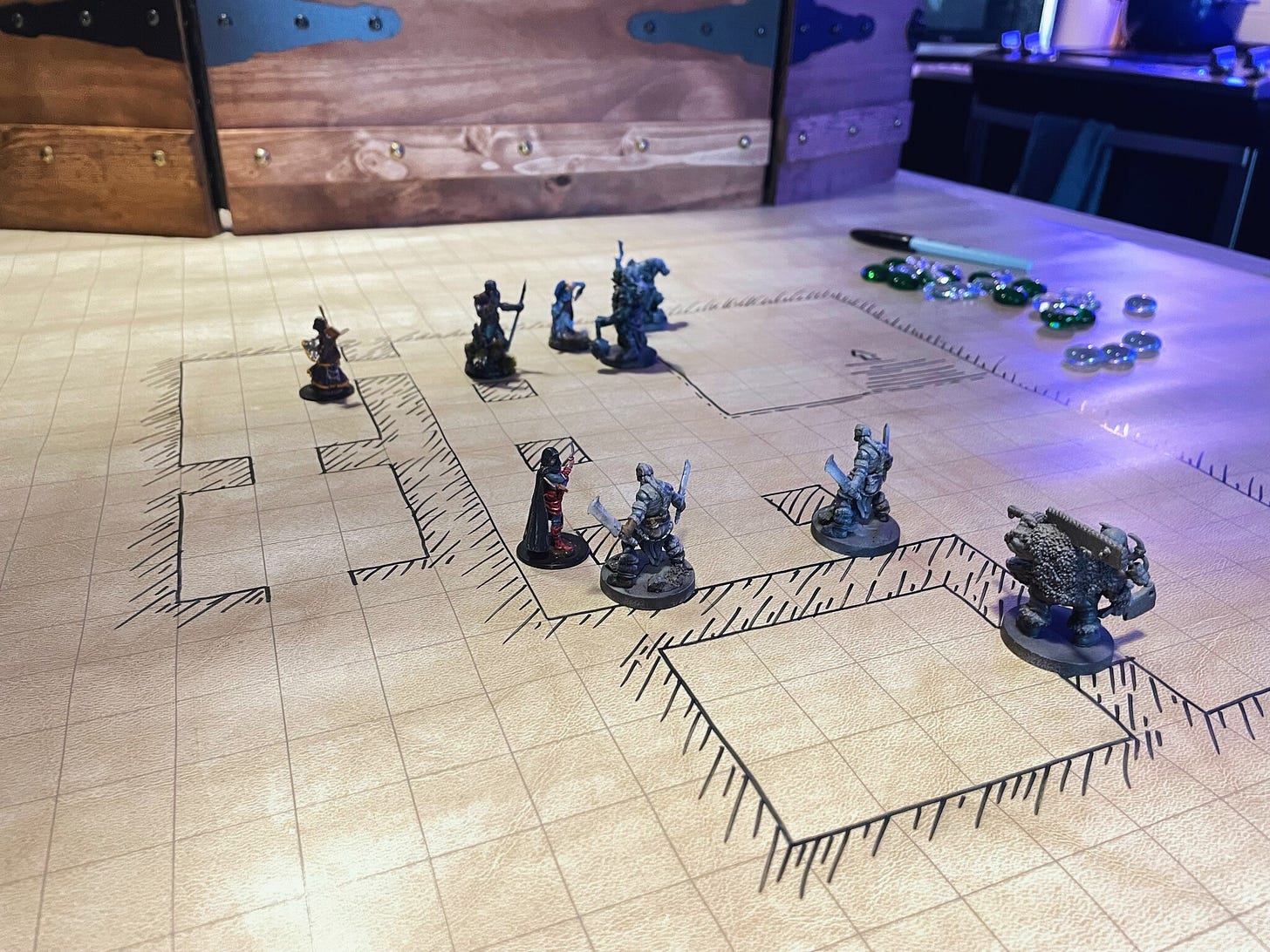

When we talk about terrain, we’re usually talking about using models and miniatures to run/represent your combat encounters. Dungeon tiles, battlemats, that kind of thing. Mostly-dead bear carcasses if you’re a big Dimension 20 fan.

Sometimes we talk about terrain in a more universal sense as the interesting, interactive place where your combat encounters take place. Now this idea – that the space where your fights take place should influence them – is pretty important to using physical terrain, but that is not what this article is about. We’ll talk sometime soon about designing interesting combat encounters, and my commentary on combat environments will live there. This one is just about representing your combats physically with props.

Theater of the mind

Now, some folks run their whole game without any physical representations of combat at all. They do this very successfully, and they have a lot of fun with it. That said, I do not recommend it.

I’ll preface this next take with the following: theater of the mind has never been a particularly influential part of my D&D culture. The DMs who taught me to play all used battlemats or terrain, and I run that way almost exclusively. I haven’t built up the skills, the techniques, or the ways of thinking that make theater of the mind work better at other tables.

So with my bias clearly stated, here’s my take: I don’t like theater of the mind for D&D. The primary concern of this system is combat, and the rules that this system uses to run combat are themselves concerned with precise physical locations. Rules for range and for area of effect, for cover and for flanking, for so many things in this game, rely on everyone having a practically mathematical understanding of where every combatant is.

As a player, I get confused in big combats using theater of the mind. As a DM, I get sloppy when I run combat in theater of the mind. I start to disregard how things like cover and flanking work because they’re dependent on me and the players sharing an understanding of combatants’ relative locations. When I disregard those systems, I make my players’ choices more shallow and less interesting.

If you are happily running theater of the mind, do not let me stop you. I just cannot help but feel that, if your group prefers theater of the mind, there are systems out there with combat engines that are not built so completely to take place in a clearly defined physical space.

4th Edition took a lot of heat for changing its language from feet of in-universe space to squares of distance at the table (ie, an attack having a range of 2 squares rather than 10 feet). I understand the resistance to using that kind of language in a sourcebook. But to be completely frank, I don’t think that 5th Edition is any less insistent that you play on a grid. It’s just less honest about it.

So how do we start representing combat?

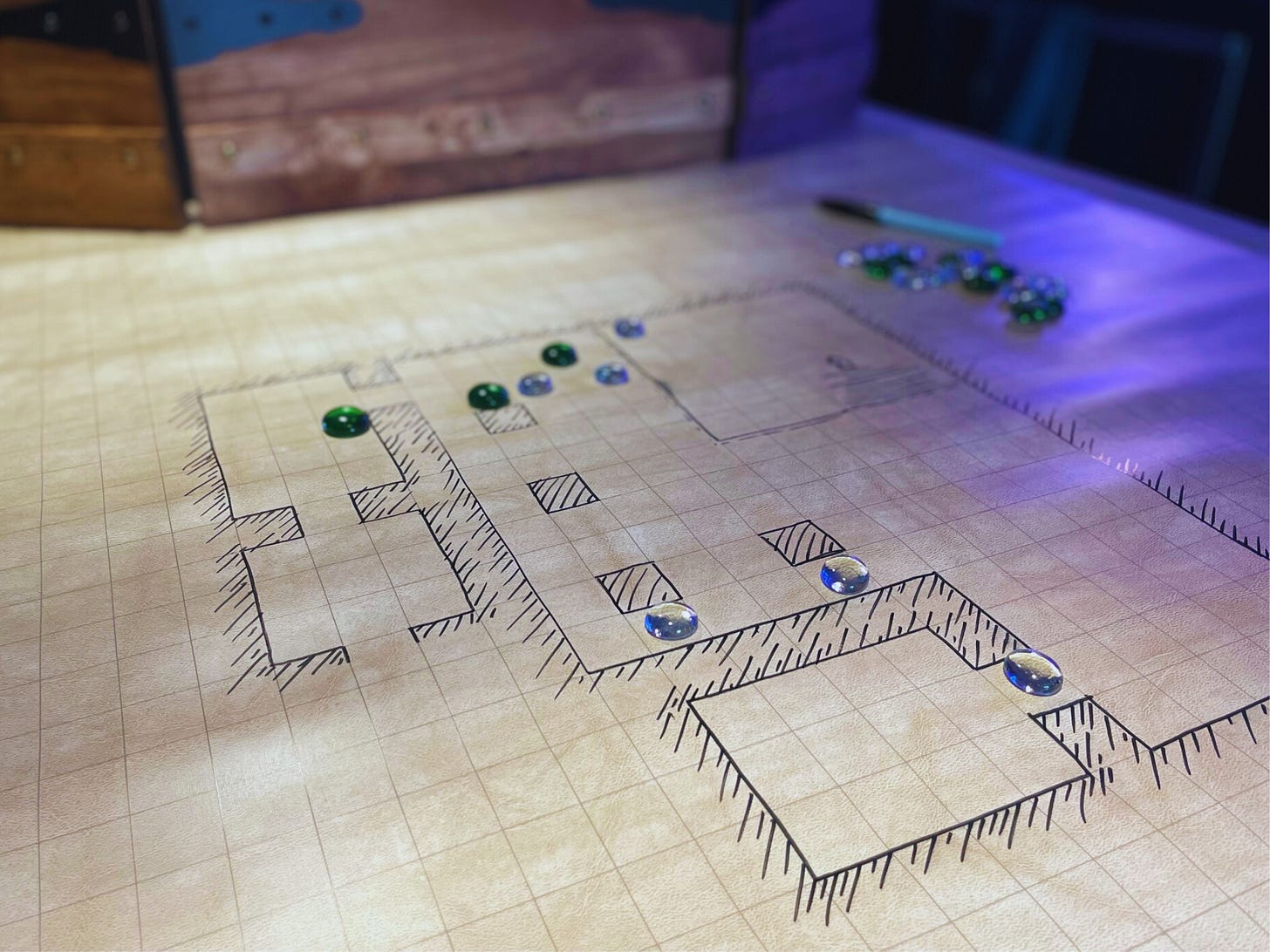

Getting on the grid without any gear can be intimidating. With absolutely zero investment, I think that your best bet is going to be theater of the mind augmented by loose sketches on grid paper. When you open a combat, rough out the shape of the enviornment and note the locations of the characters involved. As you run combat and people start to move around, update your sketches or draw new ones whenever it improves clarity. This is the way I run the occasional low-consequence combat encounter when I’m not going to draw out a full battlemap.

That said, I would make buying a wet-erase battlemat a top priority. Chessex is best-in-class here, and they offer smaller and larger mats that I think are both excellent starters for different kinds of DMs. These are super portable, super versatile gridded mats that you can draw on with wet-erase markers. With one of these, you’ll be able to get practically any of your combats mapped out. If you take care of your mat, it will stay pristine for years (please erase your maps between sessions; I know how tempting it is to just let them sit).

You can mark out characters on your mat with any kind of tokens (the iconic example being candy baddies that you get to eat on a kill), but I think a really solid place to start is with flat-bottom glass beads. The kind that come with mancala boards or cover the bottoms of abusive aquariums. They come in a ton of different colors, which makes them great for distinguishing between characters in combat. You can also get loads for super cheap.

If you get set up with both of these, I think you’ll already be able to get most of the advantage out of gridded combat, and it’ll look pretty damn classy at the table too.

What if we want to be fancy?

Let's say you get a mat. Running combat is faster, easier, and more dramatic. You want more. You want trees and rocks and towers and caverns. You want your encounters to be spectacular.

Obviously, I approve of this instinct. If you want to upgrade your setup with practically no work on your part, buy my stuff at Cutie Fest next month ;)

I’m going to assume that’s not the move for most of you though, so let’s talk about more accessible options.

Really, I think most people’s next step after a battlemat is going to be miniatures, not terrain. Players love having miniatures that match up to their characters, and DMs love having easily-readable encounters that put some of the burden of being evocative (evocation?) on props.

This article is about terrain not minis, but here are some rapid-fire thoughts. If you’re a DM looking for bad guy miniatures, go look at Steamforged Games’ Epic Encounters. They are the best on the market for filling out a collection of antagonistic miniatures. If you’re looking for heroic miniatures, the most popular options are Wizkids and Reaper. I think both are fine. Wizkids has more detailed sculpts, but those sculpts get absolutely mangled by poor production quality. Reaper features more simple and stylized figures that are much better suited to simple printing. I personally prefer smaller outfits like Dark Sword, but it gets exponentially more complicated to look for miniatures when you aren’t looking at a major brand.

Back to terrain. A good early get is a set of dungeon tiles. These are modular terrain tiles used to create the shape of enclosed spaces, caves, castles, and all manner of dungeon environments. Unfortunately, there aren’t any mass-market dungeon tiles I can really recommend.

The prestige option is Dwarven Forge. I’ve played in a couple of games using their tiles. Their work is quite pretty and quite popular. It’s also very expensive, and I have some problems with its design. Individual tiles are very small, which makes assembling spaces take longer and tends to encourage you to build encounters into highly confined spaces. This would be limiting but acceptable, if the tiles did not also have walls. In general, dungeon tiles with walls block players’ lines of sight and make positioning miniatures a big hassle. When you’re also being encouraged to create small environments, they make your whole terrain setup unreadable.

I think you’ll get better results from flat cardboard options like Wizards of the Coast’s official tilesets than you will with prestige sculpted options, but this specific product has always felt very cheap and eclectic to me. If you find a set of tiles you like, let me know, but for now, I’m going to suggest making dungeon tiles as your first foray into crafting terrain.

Location-specific battlemats can be fun too. These battlemat books are super handy. For populated spaces, these paper-craft buildings fill out a good-looking table of terrain without much effort. You can get totally playable model evergreens from the dollar store around Christmas.

For small interior details, I really like Terrain Crate. They sell themed boxes of accessory items that lend a lot of life to environments. This does rely on you already having environments to accessorize.

That’s really about all the purchased terrain I can recommend, because…

I like to make most of my own terrain.

One of my favorite things about DMing is that it’s a kind of syncretic hobby. You can take whatever passions you have, whatever disparate mediums you dabble in, and fold the products of your work into games. When I’m on a fiction writing kick, I can write in-world texts for my setting. When I want to try out audio editing, I can splice together fun audio effects for climactic moments in my campaign. When I feel like painting small stones to look like big stones, I can craft terrain that makes my combat encounters epic.

Making terrain is something that I enjoy the process and craft of, setting aside the resultant game props. I find it an exciting medium to learn and to experiment in, and a massively relaxing one to do familiar work in. I think you should try it. If you like it, you’ll have a new line on the coolest possible terrain for your game. If you hate it, you don’t ever have to do it again, and you’ll probably have a set of dungeon tiles you can use (however begrudgingly).

Most terrain crafters that I know of do most of their work out of XPS (extruded polystyrene foam). This is the same material as the flaky styrofoam packaging made of lots of little bubbles, but it’s extruded as a solid whole rather than expanded from many small beads. You can find it sold in large quantities as insulation foam (if you live in the US, it’ll be pink) or in small quantities as poster board.

If you’re just testing out this hobby, here’s your first project:

Go to the dollar tree and grab a couple of white foam poster boards. Bring them home, put them in a warm shower, and peel the paper off both sides. What’s left is the base material for your new dungeon tiles.

Use a ruler and a utility knife to chop the foam into the shape of your tiles. I like three inch squares. Cut twice as many pieces as you want tiles, as we’re going to be making the tiles two layers thick so they stay flat.

Use your ruler and a pen to score/carve 1-inch grid lines into the foam. Now we crunch some tin foil into a little ball, and roll that across the foam with a little pressure to add rocky texture. One of the best things about XPS is how well it takes carving and texture.

The pieces you’ve been texturing have probably started to warp and bend from all this abuse, so we’re going to fight them back into shape now. For every piece you’ve textured, take an untextured piece of foam the same size, and glue the two together. Use Elmer’s white glue, and apply it nice and thin with a paintbrush. Give it lots of time to dry. The end result should be a thicker, flatter tile.

That’s the shape of your tiles finished now. To give them a bit more strength and get them ready to paint, we prime with a mixture of matte Mod Podge and black acrylic paint (the cheap kind from the dollar store). Mod Podge makes the tiles strong and lets paint stick to them. Black paint saves us from having to paint over this primer with a base coat of paint.

Painting is the most difficult part of this process, but these do not need to be especially beautiful. The big skill to grow here is Dry Brushing. We take a paintbrush, get some gray paint worked deep into it, and then run our paintbrush aggressively across a paper towel until most of that paint is gone.

Take that mostly de-painted brush and use it to paint your tile. Use a fair bit of pressure, and try to paint mostly in one direction across the tile. The brush should catch and highlight the most raised sections of the tile while leaving cracks and crevices dark.

Mix up a lighter grey paint, and use that to dry brush the tile too. Use a little less pressure, so it catches a smaller amount of the tile. Keep working your way lighter in color and lighter in pressure until you’re happy with how your tile looks.

I understand that text might not be the best medium for this tutorial, so I’m kind of planning to revisit this when I next make some tiles and can take step-by-step pictures. Until then, message me if you’ve got any questions. Seriously. If you want to try this, message me or comment below. I would be so excited to help get you started making stuff.

So now you’ve got some terrain

You bought a wet-erase mat, you made some dungeon tiles, and you’ve started to build or buy dramatic pieces. When do you actually use them? When do you make a combat involved, and when can you keep things nice and simple?

Most of the time, I think it’s best to use at least some terrain.

We talked before about props and when to use them. We said that the best props are the ones that we the players interact with in the same way that our characters do and that focus player attention on the same places that our narrative and mechanics want them to focus. Terrain is in and of itself evocatively interactive. We don’t get to stand inside a foam cave, but we do get to move our character through it and better embody their experience. It is also naturally focus-affirming. Dungeons & Dragons, as a game, is about combat. Ninety percent of your characters’ abilities only matter in a fight, and a vast majority of the system’s actual mechanics are strictly about combat. It is a toolset for telling stories about fights. For that reason, I think that any story you are trying to tell using D&D should be in large part about fighting. If your narrative and the mechanics of the game both want player focus to be on combat, using terrain is going to help build and affirm that focus.

So for most fights, at least draw out a map on your battlemat. Throw down a few dungeon tiles. Get players on the grid so they can (a) make mechanically informed decisions and (b) know that combat is worthy of their attention.

That said, it’s fine for some small fights not to be represented. Sometimes your players are going to stumble into a minor scuffle that isn’t really leading anywhere. Sometimes you’re going to introduce a fight just to adjust the pacing of the adventure. Sometimes you just want players to lose a couple spell slots. When fights are frequent, not every fight should be climactic.

Just be aware that not using terrain when you do at other times use terrain signals to players that this combat is of lower consequence than those you put on the grid.

As for big terrain pieces, I say use them if you have them. If you have the chance to make your fight more represented and more rad, go for it. One caveat to that: if it’s going to take you twenty minutes to set up terrain for a mid-consequence battle that you don’t expect to take longer than half an hour, just draw it out on the mat. While it’s better for most encounters to to be represented in some way, it’s not worth breaking flow at the table to make a minor encounter perfectly represented. Save those time-consuming terrain setups for game-changing fights.

You should also try not to let your lack of terrain ever stop you from running a particular narrative beat. It can be easy, once you’ve built up a terrain collection that you’re proud of, to let that collection help to dictate what encounters you can run. If you’ve got a set of really gorgeous trees, all your fights might start to happen in forests. If you’ve got some gorgeous skeleton miniatures, there might start to be skeletons in every dungeon.

Terrain and miniatures are one set of tools that help make your storytelling more effective. They are not the be-all and end-all of what stories you can effectively tell. While there’s nothing wrong with appraising your tools and deciding that you are more equipped to tell some stories than others, D&D is an improvisational medium, and its stories frequently veer in unexpected directions. Don’t feel the need to restrict the natural flow of your story just because it’s taking you in a direction you don’t have the terrain to represent perfectly.

This is one reason that, even when running encounters I could set out in meticulous detail, I will sometimes cut my representation back to just the battlemat. It's about setting expectations for yourself and your players so that when your terrain necessarily becomes simpler, everyone at the table is already accustomed to it.

Wrapup

Those are most of my thoughts on terrain right now. Because I’m a hobbyist, I have kind of let my terrain situation spiral into absurdity. I hope that I’ve managed to present here that that’s not necessary for a well-run game, and I hope I’ve also managed to stress how much representing your combat in simpler ways really can help your game. Dungeons & Dragons is so much a wargame, and a wargame lives so much in its positioning that maps and terrain are just such immediate boons.

I’m still getting back into the swing of writing these, and I’m a little nervous that the whole structure of this article was a mess. I think all the pictures will distract from that, thankfully.

It’s been a long while since I posted anything here. A lot of that has been for the reasons you’d expect. My initial hyperfixation on writing these articles passed, and my new projects started hitting. I LARPed for the first time. I started to work on my terrain for this market. I started working on some of my fiction again. Other creative projects had my creative energy.

There’s a less direct reason too.

I haven’t used my social media much for advocacy in the past. I feel strongly and I believe strongly and I try and engage in my community when I can. But my own social media pages have never felt like spaces where I have a particularly valuable voice. It’s not a platform where I’ve felt that I had any pull.

Yet a few months ago, with the genocide in Gaza ongoing, I was using my social media feeds to promote my blog.

Doing that was an acknowledgement that my social media presence did have some kind of pull. Implicit in my personal advertising was the fact that there were people seeing my social media feed whose experience/actions I could change by posting.

Using that voice, however minimal it was, to write about games and to promote myself suddenly felt very selfish.

For some reason, instead of starting to use that voice to spread information and opportunities to help, I just stopped saying anything at all. I went back to acting like my social media feed was useless.

That wasn’t the right call. I’m still trying to be a writer, I’m still trying to be an artist, and I still get to do that when the world sucks. And if I have any voice at all, I need to use it support the cause of a free Palestine in any way that I can.

So I’m back to writing here, and I’m back to posting on my Instagram. I’m also ready to actually go and do things to help in the real world. Please go and protest. Please go and donate. Please do what you can to make things better. I’m not always very good at that. I’m trying to be better.

I’ve missed writing for y’all. Thanks for reading. Sending you my love.

Thanks for sharing these tips. Fully agree that D&D 5e needs a physical representation with a grid for the combat to really work. Theatre of the mind only really works with that system in very small-scale battles. A question about the big set-piece maps with all the crafted terrain, from someone who has never had the pleasure of using one: They look incredible, but do you feel there's pressure on you and the players to direct the narrative towards a huge battle? I feel like in some cases, the conflict could be resolved by negotiation, stealth or retreat, but bringing out the amazing physical map means a player might feel bad about doing anything other than fighting on an epic scale. And do you ever prepare a fantastic battlemap only for the players to never go to that place?

Great advice!